Today’s bestsellers are tomorrow’s remainders and Forgotten Bestsellers will run for the next four weeks as a reminder that we were once all in a lather over books that people barely even remember anymore. Have we forgotten great works of literature? Or were these books never more than literary mayflies in the first place? What better time of year than the holiday season for us to remember that all flesh is dust and everything must die?

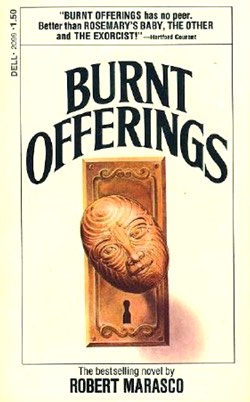

The Seventies! High inflation! Rising unemployment! The Oil Crisis! Spiking energy prices! The Recession! Desegregation of Schools! Which led to white flight! High crime! The Son of Sam! Everyone was worried about money! Which is why the Seventies were the decade when the haunted house novel thrived. There was The Sentinel (’74) about a model who moves into a new house…from hell. There was The Shining (’77) about an economically strapped family that took a last chance job in a hotel…from hell. There was The Amityville Horror (’77) about an economically strapped family that got a real estate deal…from hell. There was The House Next Door (’78) about nouveau riche suburbanites who built the contemporary home…from hell. But it all started with Robert Marasco’s Burnt Offerings (’73) about a family that escapes the city to move into the summer rental…from hell.

Marasco was a high school English teacher, which meant any illusions he’d ever had about human nature had long since been stomped to death. His two contributions to American letters were Child’s Play and Burnt Offerings. The first was a play about a war of wills between two high school teachers that involves self-mutilation, blindings, impromptu crucifixions, rumors of demonic possession, and a couple of defenestrations. Marasco said he wrote his play “to scare the hell out of everybody” and apparently it worked, running for 343 performances on Broadway. A few years later he delivered Burnt Offerings.

Originally written as a screenplay, Burnt Offerings is a slender 264 pages and was originally intended to be a black comedy, but, as Marasco said in an interview “It just came out black.” Reviewers either panned it or patronized it, but it didn’t matter. The book caught on and helped spawn the wave of haunted house novels that came out later in the decade. Stephen King’s The Shining and Jay Anson’s The Amityville Horror are both basically rewrites of Marasco’s book.

If social and political anxiety spawns zombies, economic anxiety gives birth to haunted houses and Marasco created the now-common real estate nightmare haunted house scenario: a cash-strapped family (or individual) gets a deal on a place that’s above their socio-economic station. Hoping to make a fresh start, they go all in, and in short order realize that their attempt to buy a better life at a discount is the worst decision they ever made and all they can do is run for their lives, abandoning their investment.

If there’s any doubt that Burnt Offerings is all about the square footage, the first chapter is a long lament from Marian Rolfe, trapped in their stifling Queens apartment as summer begins, her neighbors driving her bonkers as they jam the courtyard yelling to each other like a bunch of low class heathens and peeing on the mailboxes. Marian likes the finer things in life, like collecting antiques and giving her son, David, neuroses about cleanliness. Her husband, Ben, agrees to go look at a summer rental she finds, and when it turns out to be a decrepit mansion at a bargain price, he gets bullied into taking it for the summer against his better judgment. Deals like that don’t come for people like them.

The house is owned by the Allardyces, a middle-aged brother and sister who are the very epitome of shabby chic Waspy eccentricity, and they have one condition: their elderly mother lives upstairs and could the Rolfe’s please leave a tray for her three times a day. Ben sees this as the giant red warning flag it is, but Marian has to have the place and she’ll agree to anything. Once they move in (along with Ben’s elderly Aunt Elizabeth) the house immediately transforms them into their own worst nightmares. Marian begins to clean obsessively, hypnotized by the house’s silver tea services and expensive, uncared for antiques. Aunt Elizabeth, a real live wire at the start of the book, becomes frail and infirm. David gets more and more timid. Ben becomes the kind of father he never wanted to be, practically raping his wife one night, and bullying David into “being a man” and nearly drowning him in the pool. But every day the house looks nicer, newer, cleaner, and brighter.

The Seventies saw America’s cities crumble and middle class folks fleeing to the suburbs, and the class and racial overtones of this flight are scattered throughout Burnt Offerings. When informed that the house is for rent to “the right people,” Ben immediately responds, “Racist pigs.” Renting the Allardyce house isn’t their only option for a summer escape but Marian is repulsed by their middle class alternatives. A summer of public beaches and maybe two weeks in some upstate rental surrounded by all the other proles fleeing Queens makes her gag. She doesn’t want to climb the social ladder, she wants to skip a few rungs and go directly to Mansion. She wants elegance, privacy, and all the things the Allardyces have but don’t seem to appreciate.

What Marian doesn’t realize is that she’s not the owner of this house, she’s its servant. Her summer is spent on her knees, waxing floors, dusting picture frames, repairing damage. To her, it’s an act of ownership, but as is made clear by the end, she can never escape her station. The cruel truth is that the Allardyces have money and she doesn’t and nothing will change that reality. She can live in their house, she can polish their furniture, but she’ll never belong.

Most of us remember Burnt Offerings from its lugubrious 1976 movie adaptation starring a snippy Karen Black, Oliver Reed’s drifting accent, and Bette Davis fighting over the crown for Drama Queen with Burgess Meredith. A few images, like a grinning, sunglasses-wearing, cadaverous chauffeur, and its ridiculously violent shock ending have stuck in people’s minds over the years, but mostly it’s a sleepy, slow-paced haunted house movie that doesn’t do anything wrong, but doesn’t do a whole lot right, either. Which is why I was so surprised to read the book. Because it is cold-blooded.

Marasco’s page-turner is vicious, not pulling a single punch as Marian runs her hands possessively over the house, letting her family alternately either die or go insane without batting an eye. “Oh, how annoying,” she seems to think as the human damage piles up around her. “I really must polish this silver.” Shirley Jackson and Richard Matheson had written haunted house books before Marasco and The Haunting of Hill House (’59) and Hell House (’71) are both genre classics, but neither of them has a thing to say about money. Both books were about psychic investigators going to abandoned mansions and trying to figure out how they got so spooky, revolving around “are these ghosts real or am I insane” issues. It took Marasco and his now-forgotten bestseller to realize that the real issue for most people with a haunted house is, “Can I get my investment back, or did I just totally screw over my family?”

As far as I can tell, Marasco was the first American writer to bring anxieties about class, mortgages, and equity to the forefront of the haunted house novel, paving the way for the writers who came after him. Both Jay Anson’s The Amityville Horror and Stephen King’s The Shining are basically rewrites of Burnt Offerings, both of them about cash-strapped families who get deals on new places far outside what they should reasonably expect to afford and both of them coming to regret it. Because when you’re dealing with a haunted house, it doesn’t matter how much money you put into repairing that boiler or how much time you spend fixing that pool. At the end of the day, all you can do is run.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today and his latest novel is Horrorstör, about a haunted Ikea.